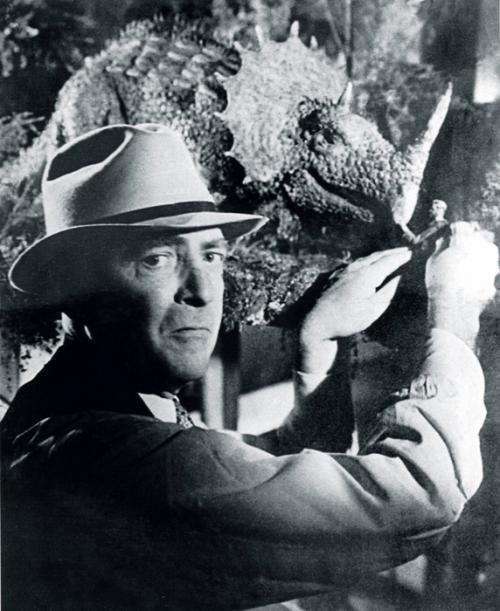

Willis O’Brien

1886-1962

USA

Pete Peterson

1903-1962

USA

King Kong is one of the most famous monsters in the history of film. The man who brought him to life, Willis O’Brien, is somewhat less well-known. His film works fall into approximately three levels of exposure: 1) VERY FAMOUS (King Kong), 2) cult favorites (The Lost World, Son of Kong, and Mighty Joe Young), and 3) mostly anonymous (everything else, detailed below). While the films’ exposure may vary, his themes were consistent: Essentially all of O’Brien’s works involve dinosaurs and/or giant monsters

O’Brien was a stop-motion animator and special effects technician, but not a director, outside a few early short films; however, he often had a much greater impact on the films that featured his work than the directors themselves. Typically, O’Brien and his assistants provided the animation for the respective films’ title creatures; in other words, O’Brien was essentially the star of the films on which his skills were employed, even though he received no onscreen credit in The Lost World or King Kong.

This article covers all of O’Brien’s film projects, realized and unrealized, and concludes with a section dedicated to the obscure work of assistant Pete Peterson.

1915-1917: The Caveman Series

O’Brien’s career began with several shorts, produced for Thomas Edison’s Conquest Films, featuring cavemen and dinosaurs, decades before The Flintstones or One Million years B.C. Unfortunately, all but three of the films are lost. Unlike his later hybrid work, the shorts are fully animated, with no live-action elements. The concept is practically identical to Hanna-Barbera’s The Flintstones, involving smallish dinosaurs peacefully coexisting with caveman stereotypes, and with prehistoric times being used to comment on then-modern society.

The Dinosaur and the Missing Link

Prehistoric Poultry

R.F.D. 10,000 B.C.

During this period, O’Brien also provided brief stop-motion effects for various Edison/Conquest films. Most are lost, but an example can be seen in the final seconds of “The Puzzling Billboard.”

1919: The Ghost of Slumber Valley

O’Brien moved on from Edison, teaming up with producer, co-director, and co-writer Herbert M. Dawley for an ill-fated short, originally intended to be a feature, called “The Ghost of Slumber Mountain.” For the first time, he portrayed dinosaurs as big, vicious monsters, as opposed their cartoonish portrayal in his future films. Even with its short running time, “Ghost” mostly rambles around, notable only for O’Brien’s rather limited footage. While the film may not be great, it surely provided experience for O’Brien’s first feature, released six long years later.

1925: The Lost World

Ten years into his career, O’Brien really got going when provided with the opportunity to work on the first feature-length dinosaur epic, The Lost World, based on the book by Arthur Conan Doyle. (Why Michael Crichton and Steven Spielberg felt the need to appropriate the name remains beneath them and Satan.) The plot involves a long distance expedition to an isolated location where dinosaurs still roam. O’Brien animated all kinds of dinosaur mayhem, including massive fights. The final act includes, as far as I can tell, the first giant monster rampaging through a city sequence. In other words, it contains many of the elements that would be repeated eight years later in Kong. By now you may have noticed a trend of sizable gaps between projects. Unfortunately, this work rate would plague O’Brien throughout his career.

1931: Creation (test footage)

In the early 1930s, O’Brien began another dinosaur film, entitled Creation. As you can see above, some of the test footage still exists.

1933: King Kong

Creation was canceled, more or less, and the models and some of the concepts were rolled into the new production, King Kong, overseen by co-producers and co-directors Merian C. Cooper and Edward B. Schoedsack. The new film was essentially Lost World turned up to 11. The characters were more memorable, the action much more intense, and, in the middle of all of those crazy dinosaurs, there was a much more charismatic and relatable monster (guess who?). King Kong is O’Brien’s magnum opus and his legacy, and it’s not by accident, as it’s his most ambitious and thrilling work (even he was credited on screen, ugh).

Kong has proven to be massively influential, producing a half dozen official sequels, plus several ripoffs like Konga, Mighty Peking Man, A*P*E, and Queen Kong, plus homages, i.e. the climaxes of Mad, Mad, Mad Monster Party and Flesh Gordon (see below). Additionally, it paved the way for just about film about a giant monster causing havoc and fighting other giant monsters, most notably the Godzilla series.

1933: Son of Kong

Kong was such a massive hit that RKO pumped out a cash cow sequel, released in the same calendar year, just 9.5 months after the original. O’Brien must have been beside himself; he hadn’t enjoyed such quick turnaround between jobs since his days at Conquest. The quick production was made possible by a much less ambitious script, as well as a 69 minute running time, compared to the 100 minutes of the original. The stop-motion doesn’t even begin until about 40 minutes in, but the ride is worth it for the final half-hour, which packs in a lot of mayhem, not to mention Kong’s son, concluded by a major cataclysm that seems to have been designed to end the series for good.

Defying reason, the release of Son of Kong marked the beginning of the longest dry spell of O’Brien’s career, at least from a stop-motion perspective. He provided practical and technical effects for some other Cooper films like The Last Days of Pompeii and The Dancing Skeleton, but his formidable skills with stop-motion were allowed to go criminally unused.

Meanwhile, Ray Harryhausen, a young man who would become known as something of an O’Brien protege, was beginning his ascent. When young Harryhausen showed some of his work to O’Brien, the latter considered the former to be a potential threat from a competition standpoint, and his fears came to pass. A true self starter, Harryhausen took it upon himself to produce a series of short, fully-animated films based on famous fairy tales while O’Brien did who-knows-what.

This proved to be a fundamental difference between the two: Harryhausen was the instigator of all but three of the features he worked on, while O’Brien was hired onto all of his features. In his defense, though, he did attempt to get some full-length films of his own off the ground, but it never worked out (more on that below). One other difference: While both men had a predilection for large creatures, O’Brien may have been a bit too devoted to his beloved dinosaurs.

1949: Mighty Joe Young

When O’Brien was finally called for another project, it ended up being another giant ape movie, working once more under Cooper and Schoedsack. Even King Kong and Son of Kong veteran Robert Armstrong was back on board. There was a newcomer, though: the upstart rival, Harryhausen!, in the role of an assistant. O’Brien had another assistant at this point, the man with the awesome name, Pete Peterson.

Mighty Joe Young is almost a toned down remake of King Kong. The dinosaurs are replaced by cowboys and lions. Joe is much smaller than Kong, and the violence is greatly diminished. The animation, handled largely by Harryhausen under O’Brien, is smooth, and Joe has a very different personality than Kong. The completed film has its merits for fans of the genre, but fails to amaze, which probably affected its business (it was something of a flop).

After Joe‘s release, O’Brien and Harryhausen went their own ways. The latter returned to his fairy tale shorts before being hired on to The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, a job that probably would have gone to O’Brien in Harryhausen’s absence. The protege moved on to It Came from beneath the Sea, while O’Brien . . . sat at home?

1956: The Animal World (excerpt)

In 1956, Harryhausen threw O’Brien a bone and invited him to collaborate on a 10-minute sequence for the film, The Animal World, featuring – you guessed it – dinosaurs. The content resembles most closely The Lost World. It contains some of the usual antagonistic dino shenanigans, but doesn’t make a huge impact given that O’Brien had been there so many times before.

1957: The Black Scorpion

Amazingly, O’Brien didn’t have to wait years and years for his next job, as he was scooped up for The Black Scorpion. Overall, the film is O’Brien’s worst to date, but looking strictly at the stop-motion work, it’s a doozy, blowing Mighty Joe Young out of the water. The handful of giant black scorpions, including a super giant, look great and are extremely destructive. The non-stop-motion scorpion facial closeups are pretty dire, and used way too much, but I’m not sure if O’Brien had anything to do with them.

The dialogue and acting, combined with the annoying pseudo-Mexico setting, are difficult to tolerate, the monsters make up for it. Some of the unused oversized arthropods from King Kong finally make their debuts. The highlight is a massive, very impressively animated battle between the alpha black scorpion and four tanks, all inside of Mexico City’s famous Estadio Azteca. The scene deserves to be famous; instead, it’s practically unknown.

1959: The Giant Behemoth

O’Brien only had to wait two years for his next project, which, sadly, proved to be his last. Oddly, The Giant Behemoth is practically a remake of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. The two releases even shared the same director, Eugene Lourie, which is especially perplexing. Both films feature huge, reptilian monsters who can fire energy attacks from their mouths. The anti-monster strategies employed by the protagonists are practically the same.

This strange development allows for something of a direct comparison between O’Brien and Harryhausen. Beast is a better movie overall, but strictly comparing monsters, O’Brien comes ahead. There’s some aspect of the Behemoth that’s more intimidating, maybe the muscle tone, or his lighting technique, or his models, watching the Behemoth parade around brings back memories of Kong, and that’s a great thing. Incidentally, Lourie went on to direct another giant reptile-trashing-a-city movie two years later: Gorgo, which is a much better film than either Beast or Behemoth.

Unrealized Projects

Even though most of O’Brien’s projects came to him, he did attempt to make his own ideas happen. Oddly, some of his concepts did make it to the screen, just without his direct involvement; for example, the 1956 film, The Beast of Hollow Mountain, was based on an original O’Brien story pitting cowboys (a la Mighty Joe Young) against dinosaurs (big surprise). Amazingly, the producers went with a different effects supervisor! Harryhausen’s 1969 film, The Valley of Gwangi, is based on the same story.

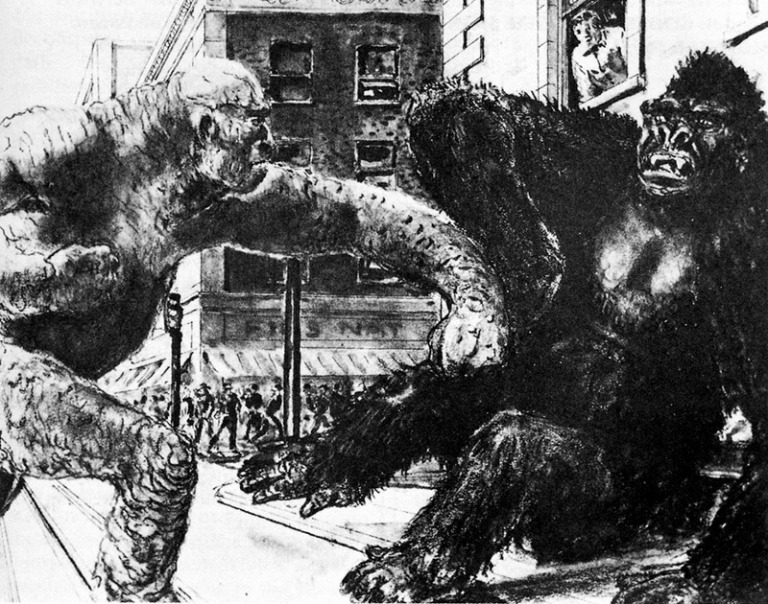

King Kong vs. Godzilla, released by Toho in 1962, was actually based on O’Brien’s concept called King Kong vs. Prometheus (another name for the Frankenstein monster). His script was stolen and sold to Toho behind his back. The poor man just couldn’t catch a break.

O’Brien also had at least one major project that was never produced by anybody. In the late 1930s, he worked with Cooper on War Eagles, which would have been an awesome film. The story involves vikings riding on giant eagles and fighting – you guessed it – dinosaurs. Unfortunately, those jerks Hitler and Hirohito ruined it all by starting World War II. As one would expect, given O’Brien’s fortunes, the project was never resumed after the war.

1958-1960: Pete Peterson Unrealized Projects

The Las Vegas Monster

The Beetlemen

O’Brien’s assistant had some ideas of his own. Just as O’Brien had done with Creation, Peterson created test reels in an attempt to get his projects rolling. Naturally, neither test reel resulted in a feature film, at least not as Peterson had intended. Years after his and O’Brien’s deaths, puppets and armatures from both test reels were used by Harryhausen proteges Jim Danforth and David Allen in the awful sexploitation film, Flesh Gordon.

The under-utilization of O’Brien’s talents is a mystery. Did he have a condition or status that kept him from being employed? Was he a communist or something? How did Hollywood producers not see endless possibilities for his talents? If anything, their imaginations and budgets only shrank as time went on. According to some of the sources, his budgets for The Giant Behemoth (1959) and The Ghost of Slumber Mountain (1919) were identical in spite of years of inflation and wide gaps in running lengths.

In spite of his relatively low output, O’Brien set the table for the later stop-motion/live action hybrid masters, including Harryhausen, Allen, Danforth, and Phil Tippett. His DNA is deeply infused in the epic fantasy film industries of the USA and Japan. In other words, watch these damned movies, even if you have to fast forward through the monsterless scenes.

©2016 Cuscowilla Conservatory

©2016 Cuscowilla Conservatory